Pravda (Russian: Правда; IPA: [ˈpravdə], "Truth") is a Russian political newspaper associated with the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. The newspaper began publication in 1912 and emerged as a leading newspaper of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution. The newspaper was an organ of the Central Committee of the CPSU between 1912 and 1991.

After the dissolution of the USSR, Pravda was sold off by Russian President Boris Yeltsin. As was the fate of many of the Soviet-era enterprises Pravda suffered a downturn and was sold to a Greek business family. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation acquired the newspaper in 1997 and established it as its principal mouthpiece. Pravda is still functioning from the same headquarters on Pravda Street in Moscow where it was published in the Soviet days. During its heyday Pravda was selling millions of copies per day compared to the current print run of just one hundred thousand copies.

During the Cold War, Pravda was well known in the West for its pronouncements as the official voice of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. (Similarly Izvestia was the official voice of the Soviet government.)

Origins

.JPG/200px-Kotlasskiy_kraevedcheskiy_musey_(093).JPG)

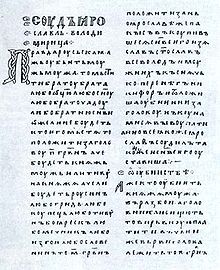

Pre-revolutionary Pravda

Though Pravda officially began publication on 5 May 1912, the anniversary of Karl Marx's birth, its origins trace back to 1903 when it was founded in Moscow by a wealthy railway engineer, V. A. Kozhevnikov. Pravda had started publishing in the light of the Russian Revolution of 1905.

During its earliest days, Pravda had no political orientation. Kozhevnikov started it as a journal of arts, literature and social life. Kozhevnikov was soon able to form up a team of young writers including A.A. Bogdanov, N.A Rozhkov, M.N Pokrovsky, I.I Skvortsov-Stepanov, P.P Rumyantsev and M.G. Lunts, who were active contributors on 'social life' section of Pravda. Later they became the editorial board of the journal and in the near future also became the active members of the Bolshevik fraction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Because of certain quarrels between Kozhevnikov and the editorial board, he had asked them to leave and the Menshevik fraction of the RSDLP took over as Editorial Board. But the relationship between them and Kozhevnikov was also a bitter one.

The Ukrainian political party Spilka, which was also a splinter group of the RSDLP, took over the journal as its organ. Leon Trotsky was invited to edit the paper in 1908 and the paper was finally moved to Vienna in 1909. By then, the editorial board of Pravda consisted of hard-line Bolsheviks who sidelined the Spilka leadership soon after it shifted to Vienna. Trotsky had introduced a tabloid format to the newspaper and distanced itself from the intra-party struggles inside the RSDLP. During those days, Pravda gained a large audience among Russian workers. By 1910 the Central Committee of the RSDLP suggested making Pravda its official Organ.

Finally, at the sixth conference of the RSDLP held in Prague in January 1912, the Menshevik fraction was expelled from the party. The party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin decided to make Pravda its official mouthpiece. The paper was shifted from Vienna to St. Petersburg and the first issue under Lenin's leadership was published on 5 May 1912 (April 22, 1912 OS). It was the first time that Pravda was published as a legal political newspaper. The Central Committee of the RSDLP, workers and individuals such as Maxim Gorky provided financial help to the newspaper. The first issue published on 5 May cost two kopeks and had four pages. It had articles on economic issues, workers movement, and strikes, and also had two proletarian poems. M. E. Egorov was the first editor of St. Petersburg Pravda and Member of Duma N.G. Poletaev served as its publisher.

Egorov was not a real editor of Pravda but this position was pseudo in nature. As many as 42 editors had followed Egorov within a span of two years, till 1914. The main task of these editors was to go to jail whenever needed and to save the party from a huge fine. On the publishing side, the party had chosen only those individuals as publishers who were sitting members of Duma because they had parliamentary immunity. Initially, it had sold between 40,000 and 60,000 copies. The paper was closed down by tsarist censorship in July 1914. Over the next two years, it changed its name eight times because of police harassment:

- Ð Ð°Ð±Ð¾Ñ‡Ð°Ñ Ð¿Ñ€Ð°Ð²Ð´Ð° (Rabochaya Pravda, Worker's Truth)

- Ð¡ÐµÐ²ÐµÑ€Ð½Ð°Ñ Ð¿Ñ€Ð°Ð²Ð´Ð° (Severnaya Pravda Northern Truth)

- Правда Труда (Pravda Truda, Labor's Truth)

- За правду (Za Pravdu, For Truth)

- ПролетарÑÐºÐ°Ñ Ð¿Ñ€Ð°Ð²Ð´Ð° (Proletarskaya Pravda, Proletarian Truth)

- Путь правды (Put' Pravdy, The Way of Truth)

- Рабочий (Rabochy, The Worker)

- Ð¢Ñ€ÑƒÐ´Ð¾Ð²Ð°Ñ Ð¿Ñ€Ð°Ð²Ð´Ð° (Trudovaya Pravda, Labor’s Truth)

During the 1917 Revolution

The overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II by the February Revolution of 1917 allowed Pravda to reopen. The original editors of the newly reincarnated Pravda, Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov, were opposed to the liberal Russian Provisional Government. However, when Lev Kamenev, Joseph Stalin and former Duma deputy Matvei Muranov returned from Siberian exile on March 12, they took over the editorial board - starting with March 15.

Under Kamenev's and Stalin's influence, Pravda took a conciliatory tone towards the Provisional Governmentâ€""insofar as it struggles against reaction or counter-revolution"â€"and called for a unification conference with the internationalist wing of the Mensheviks. On March 14, Kamenev wrote in his first editorial:

- What purpose would it serve to speed things up, when things were already taking place at such a rapid pace?

and on March 15 he supported the war effort:

- When army faces army, it would be the most insane policy to suggest to one of those armies to lay down its arms and go home. This would not be a policy of peace, but a policy of slavery, which would be rejected with disgust by a free people.

After Lenin's and Grigory Zinoviev's return to Russia on April 3, Lenin strongly condemned the Provisional Government and unification tendencies in his April Theses. Kamenev argued against Lenin's position in Pravda editorials, but Lenin prevailed at the April Party conference, at which point Pravda also condemned the Provisional Government as "counter-revolutionary". From then on, Pravda essentially followed Lenin's editorial stance. After the October Revolution of 1917 Pravda was selling nearly 100,000 copies daily.

The Soviet period

The offices of the newspaper were transferred to Moscow on March 3, 1918 when the Soviet capital was moved there. Pravda became an official publication, or "organ", of the Soviet Communist Party. Pravda became the conduit for announcing official policy and policy changes and would remain so until 1991. Subscription to Pravda was mandatory for state run companies, the armed services and other organizations until 1989.

Other newspapers existed as organs of other state bodies. For example, Izvestia, which covered foreign relations, was the organ of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, Trud was the organ of the trade union movement, Bednota was distributed to the Red Army and rural peasants. Various derivatives of the name Pravda were used both for a number of national newspapers (Komsomolskaya Pravda was the organ of the Komsomol organization, and Pionerskaya Pravda was the organ of the Young Pioneers), and for the regional Communist Party newspapers in many republics and provinces of the USSR, e.g. Kazakhstanskaya Pravda in Kazakhstan, Polyarnaya Pravda in Murmansk Oblast, Pravda Severa in Arkhangelsk Oblast, or Moskovskaya Pravda in the city of Moscow.

Shortly, after the October 1917 Revolution, Nikolai Bukharin became the Editor of Pravda. Bukharin's apprenticeship for this position had occurred during the last months of his emigration/exile prior to Bukharin's return to Russia in April 1917. These months from November 1916 until April 1917 were spent by Bukharin in New York City in the United States. In New York, Bukharin divided his time between the local libraries and his work for Noyvi Mir (The New World) a Russian language newspaper serving the Russian speaking community of New York. Bukharin's involvement with Noyvi Mir became deeper as time went by. Indeed from January 1917 until April when he returned to Russia, Bukharin served as de facto Editor of Noyvi Mir.Z In the period after the death of Lenin in 1924, Pravda was to form a power base for Nikolai Bukharin, one of the rival party leaders, who edited the newspaper, which helped him reinforce his reputation as a Marxist theoretician. Bukharin would continue to serve as Editor of Pravda until he and Mikhail Tomsky were removed from their responsibilities at Pravda in February 1929 as part of their downfall as a result of their dispute with Joseph Stalin. Similarly, after the death of Stalin in 1953 and the ensuing power vacuum, Communist Party leader Nikita Khrushchev used his alliance with Dmitry Shepilov, Pravdaâ€â€Š'​s editor-in-chief, to gain the upper hand in his struggle with Prime Minister Georgy Malenkov.

A number of places and things in the Soviet Union were named after Pravda. Among them was the city of Pravdinsk in Gorky Oblast (the home of a paper mill producing much newsprint for Pravda and other national newspapers), and a number of streets and collective farms.

As the names of the main Communist newspaper and the main Soviet newspaper, Pravda and Izvestia, meant "the truth" and "the news" respectively, a popular Russian saying was "v Pravde net izvestiy, v Izvestiyakh net pravdy" (In the Truth there is no news, and in the News there is no truth).

The post-Soviet period

On August 22, 1991, a decree by Russian President Boris Yeltsin shut down the Communist Party and seized all of its property, including Pravda. Its team of journalists sought to keep the newspaper in existence. They registered a new paper with the same title just weeks after.

A few months later, then-editor Gennady Seleznyov (now a member of the Duma) sold Pravda to a family of Greek entrepreneurs, the Yannikoses. The next editor-in-chief, Aleksandr Ilyin, handed Pravdaâ€â€Š'​s trademarkâ€"the Order of Lenin medalsâ€"and the new registration certificate over to the new owners. The relationship between the new management and the Pravda staff was never an easy one. On one instance the two Greek Investors Theodoros and Christos Giannikos were blocked by the police from entering the office premises. Finally the management took a hands off approach to the Pravda and started a new weekly newspaper Pravda Pyat. Pravda was closed down for a brief period on July 30, 1996. Some of Pravdaâ€â€Š'​s journalists established their own English language online newspaper known as Pravda Online. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation, which gained new ground in Russia after the 1996 Duma elections, finally purchased Pravda. Pravda has become an official organ of the CPRF. This was verified by the special resolution of the 4th Congress of the CPRF. Pravda is witnessing hard times and the number of its staff members and print run has been significantly reduced. During the Soviet era it was a daily newspaper but today it publishes three times a week.

Pravda still operates from the same headquarters at Pravda Street from where journalists used to prepare Pravda everyday during the Soviet era. It operates under the leadership of journalist Boris Komotsky. A function was organized by the CPRF on 5 July 2012 to celebrate the 100 years of Pravda.

Editors-in-Chief

- Lev Kamenev

- Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin, (1918â€"1929)

- Mikhail S. Olminsky

- Maximilian Alexandrovich Savelyev, (1928â€"1930)

- Lev Z. Mehlis, (1930â€"1937)

- Ivan E. Nikitin, (1937â€"1938)

- Pyotr Nikolayevich Pospelov, (1940â€"1949)

- Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov, (1949â€"1950)

- Leonid Fedorovich Ilichev, (1951â€"1952)

- Dmitry Trofymovych Shepilov, (1952â€"1956)

- Pavel Satyukov, (1956â€"1964)

- Aleksei Matveevich Rumyantsev, (1964â€"1965)

- Mikhail Vasilyevich Zimyanin, (1965â€"1976)

- Victor G. Afanasiev, (1976â€"1989)

- Ivan T. Frolov, (1989â€"1991)

See also

- Central newspapers of the Soviet Union

- Doctors' plot

- Eastern Bloc information dissemination

- Freedom of the press in Russia

- Media of Russia

- People's correspondent

- Samantha Smith

References

Further reading

- Cookson, Matthew (October 11, 2003). The spark that lit a revolution. Socialist Worker, p. 7.

External links

- Pravda Newspaper

- Some articles published in Pravda in the 1920s

- 100 Years of Pravda Video Clip

- Historic versions of Pravda from 1904â€"1942