The Epistle to the Hebrews of the Christian Bible is one of the New Testament books whose canonicity was disputed. Traditionally, Paul the Apostle was thought to be the author. However, since the third century this has been questioned, and the consensus among most modern scholars is that the author is unknown.

Ancient views

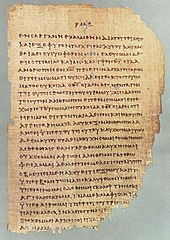

Hebrews was included in the collected writings of Paul from a very early date. For example, the late second-century/early third century codex 46, a volume of Paul's general epistles, includes Hebrews immediately after Romans.

While the assumption of Pauline authorship readily allowed its acceptance in the Eastern Church, doubts persisted in the West.

Eusebius did not directly list the Epistle to the Hebrews among the antilegomena or disputed books (though he included the unrelated Gospel of the Hebrews). However, he did record that "some have rejected the Epistle to the Hebrews, saying that it is disputed by the church of Rome, on the ground that it was not written by Paul." He also recorded the views of Clement of Alexandria, that it was written by Paul in Hebrew and later translated into Greek, possibly by Luke.

Doubts about Pauline authorship were raised around the end of the second century, predominantly in the West. Tertullian attributed the epistle to Barnabas. Both Gaius of Rome and Hippolytus excluded Hebrews from the works of Paul, the latter attributing it to Clement of Rome. Origen noted that others had claimed Clement or Luke as the author, but he tentatively accepted Pauline authorship and the explanation of Clement of Alexandria.

Jerome, aware of such lingering doubts, included the epistle in his Vulgate but moved it to the end of Paul's writings. Augustine affirmed Paul's authorship and vigorously defended the epistle. By then its acceptance in the New Testament canon was well settled.

Modern views

In general, the evidence against Pauline authorship is considered too solid for scholarly dispute. Donald Guthrie, in his New Testament Introduction (1976), commented that "most modern writers find more difficulty in imagining how this Epistle was ever attributed to Paul [instead of] disposing of the theory." Harold Attridge tells us that "it is certainly not a work of the apostle". Daniel Wallace, who holds to the traditional authorship of the other epistles, states that "the arguments against Pauline authorship, however, are conclusive." As a result, although a few people today believe Paul wrote Hebrews, such as theologian R.C. Sproul, contemporary scholars generally reject Pauline authorship. As Richard Heard notes, in his Introduction to the New Testament, "modern critics have confirmed that the epistle cannot be attributed to Paul and have for the most part agreed with Origen's judgement, 'But as to who wrote the epistle, only God knows the truth.'"

Attridge argues that similarities with Paul's work are simply a product of a shared usage of traditional concepts and language. Others, however, have suggested that they are not accidental, and that the work is a deliberate forgery attempting to pass itself off as a work of Paul.

Internal evidence

Internal anonymity

The text as it has been passed down to the present time is internally anonymous, though some older title headings attribute it to the Apostle Paul.

Stylistic differences from Paul

The style is notably different from the rest of Paul's epistles, a characteristic noted by Clement of Alexandria (c. 210), who argued, according to Eusebius, that the original letter had a Jewish audience and was written in Hebrew and later translated into Greek, "some say [by] the evangelist Luke, others... [by] Clement [of Rome]... The second suggestion is more convincing, in view of the similarity of phraseology shown throughout by the Epistle of Clement and the Epistle to the Hebrews, and in absence of any great difference between the two works in the underlying thought." He concluded that "as a result of this translation, the same complexion of style is found in this Epistle and in the Acts: but that the [words] 'Paul an apostle' were naturally not prefixed. For, he says, 'in writing to Hebrews who had conceived a prejudice against him and were suspicious of him, he very wisely did not repel them at the beginning by putting his name.'"

This stylistic difference have led Martin Luther and Lutheran churches to refer to Hebrews as one of the antilegomena, one of the books whose authenticity and usefulness was questioned. As a result, it is placed with James, Jude, and Revelation, at the end of Luther's canon.

Stylistic similarities to Paul

Some theologians and groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, who continue to maintain Pauline authorship, repeat the opinion of Eusebius that Paul omitted his name because he, the Apostle to the Gentiles, was writing to the Jews. They conjecture that Jews would have likely dismissed the letter if they had known Paul to be the source. They theorize that the stylistic differences from Paul’s other letters are attributed to his writing in Hebrew to the Hebrews, and that the letter was translated into Greek by Luke.

The epistle contains Paul's classic closing greeting, "Grace...be with you..." as he stated explicitly in 2 Thessalonians 3:17-18 and as implied in 1 Corinthians 16:21-24 and Colossians 4:18. This closing greeting is included at the end of each of Paul's letters.

In the 13th chapter of Hebrews, Timothy is referred to as a companion. Timothy was Paul's missionary companion in the same way Jesus sent disciples out in pairs. Also, the writer states that he wrote the letter from "Italy", which also at the time fits Paul. The difference in style is explained as simply an adjustment to a more unique audience, to the Jewish Christians who were being persecuted and pressured to go back to old Judaism.

Although the writing style varies from Paul in a number of ways, some similarities in wordings to some of the Pauline epistles have been noted. In antiquity, some began to ascribe it to Paul in an attempt to provide the anonymous work an explicit apostolic pedigree.

In more recent times, some scholars advanced a case for the authorship of Priscilla. This suggestion came from Adolf von Harnack in 1900. Harnack claimed that the Epistle was "written to Romeâ€"not to the church, but to the inner circle"; that the earliest tradition 'blotted out' the name of the author; that "we must look for a person who was intimately associated with Paul and Timothy, as the author" and that Priscilla matched this description. Other commentators have disagreed on the basis that the self-reference in Hebrews 11:32 employs the masculine participle, implying that Priscilla could not have been the author, unless she was masquerading as a male in order to gain credibility. Ruth Hoppin, who argues that Priscilla 'meets every qualification, matches every clue, and looms ubiquitous in every line of investigation', suggests that the masculine participle may have been altered by a scribe, or that the author was deliberately using a neutral participle 'as a kind of abstraction'.

Tertullian (On Modesty 20) suggested Barnabas as the author: "For there is extant withal an Epistle to the Hebrews under the name of Barnabasâ€"a man sufficiently accredited by God, as being one whom Paul has stationed next to himself…". Internal considerations suggest the author was male, was an acquaintance of Timothy, and was located in Italy. Barnabas, to whom other noncanonical works are attributed (such as Epistle of Barnabas), was close to Paul in his ministry.

Other possible authors were suggested as early as the third century CE. Origen of Alexandria (c. 240) suggested that either Luke the Evangelist or Clement of Rome. Martin Luther proposed Apollos, described as an Alexandrian and "a learned man", popular in Corinth, and adept at using the scriptures and arguing for Christianity while "refuting the Jews".

References

- ^ Alan C. Mitchell, Hebrews (Liturgical Press, 2007) page 6.

- ^ Richard A. Thiele (2008). A Reexamination of the Authorship of the "Epistle to the Hebrews". ProQuest. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-109-90125-2.Â

- ^ Comfort, Philip W. (2005). Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism. pp. 36â€"38. ISBN 0805431454.Â

- ^ Alan C. Mitchell, Hebrews (Liturgical Press, 2007) page 2.

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 3.25.5 (text).

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 3.3.5 (text); cf. also 6.20.3 (text).

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 6.14.2â€"3 (text), citing Clement's Hypotyposes.

- ^ De Pudic. 20 (text).

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 6.20.3 (text).

- ^ Photius, Bibl. 121.

- ^ Bar Ṣalībī, In Apoc. 1.4.

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 6.25.11â€"14 (text).

- ^ Jerome, Ad Dardanum 129.3.

- ^ Peter Kirby, EarlyChristianWritings.com

- ^ "Hebrews: Introduction, Argument and Outline", Daniel Wallace

- ^ R.C. Sproul - The Supremacy of Christ - Ligonier.org. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Ehrman 2004:411

- ^ Religion-online.org, Richard Heard, Introduction To The New Testament

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the Name of God--Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are (HarperCollins, 2011) page 23.

- ^ Rothschild, Clare K. (2009). Hebrews as Pseudepigraphon: The History and Significance of the Pauline Attribution of Hebrews. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. p. 4. ISBN 9783161498268.Â

- ^ Eusebius (1965). The History of the Church. London: Penguin. pp. #37, p.101.Â

- ^ "Canon, Bible.", Lutheran Cyclopedia, LCMS,

6. Throughout the Middle Ages there was no doubt as to the divine character of any book of the NT. Luther again pointed to the distinction between homologoumena and antilegomena* (followed by M. Chemnitz* and M. Flacius*). The later dogmaticians let this distinction recede into the background. Instead of antilegomena they use the term deuterocanonical. Rationalists use the word canon in the sense of list. Lutherans in America followed Luther and held that the distinction between homologoumena and antilegomena must not be suppressed. But caution must be exercised not to exaggerate the distinction.

- ^ a b The Argument of Hebrews - Bible.org. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ a b Hahn, Roger. "The Book of Hebrews". Christian Resource Institute. Accessed 17 Mar 2013

- ^ a b Equipped for Every Good Work â€" Lesson 66 - Hebrews â€" Watchtower Bible and Tract Society â€" International Bible Students Association â€" 1946. p. 332.

- ^ Keathley, Hampton IV. "The Argument of Hebrews"

- ^ "Introduction to the Letter to the Hebrews". [1] Accessed 17 Mar 2013

- ^ All Scripture Is Inspired of God and Beneficial - Bible Book Number 58 - Hebrews - Watchtower Bible and Tract Society â€" International Bible Students Association â€" 1990. p. 243.

- ^ Epistle to the Hebrews - Biblical Training - 23 September 2014.

- ^ Attridge, Harold W.: Hebrews. Hermeneia; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1989, pp. 1-6.

- ^ von Harnack, Adolph, "Probabilia uber die Addresse und den Verfasser des Habraerbriefes, " Zeitschrift fur die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der aelteren Kirche (E. Preuschen, Berlin: Forschungen und Fortschritte, 1900), 1:16â€"41. English translation available in Lee Anna Starr, The Bible Status of Woman. Zarephath, N.J.: Pillar of Fire, 1955), 392â€"415

- ^ Craig Blomberg, From Pentecost to Patmos, Apollos, 2006, p. 411Â

- ^ Ruth Hoppin, 'The Epistle to the Hebrews is Priscilla's Letter', in Amy-Jill Levine, Maria Mayo Robins (eds), A Feminist Companion to the Catholic Epistles and Hebrews, (A&C Black, 2004) pages 147-170.

- ^ Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 6.25.11-14 (text)

- ^ Robert Girard (17 June 2008). The Book of Hebrews. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBNÂ 978-1-4185-8711-6.Â

- ^ George H. Guthrie (15 December 2009). Hebrews. Zondervan. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-310-86625-1.Â

- ^ Thomas Nelson (21 October 2014). The NKJV Study Bible: Full-Color Edition. Thomas Nelson. pp. 1981â€". ISBN 978-0-529-11441-9.Â